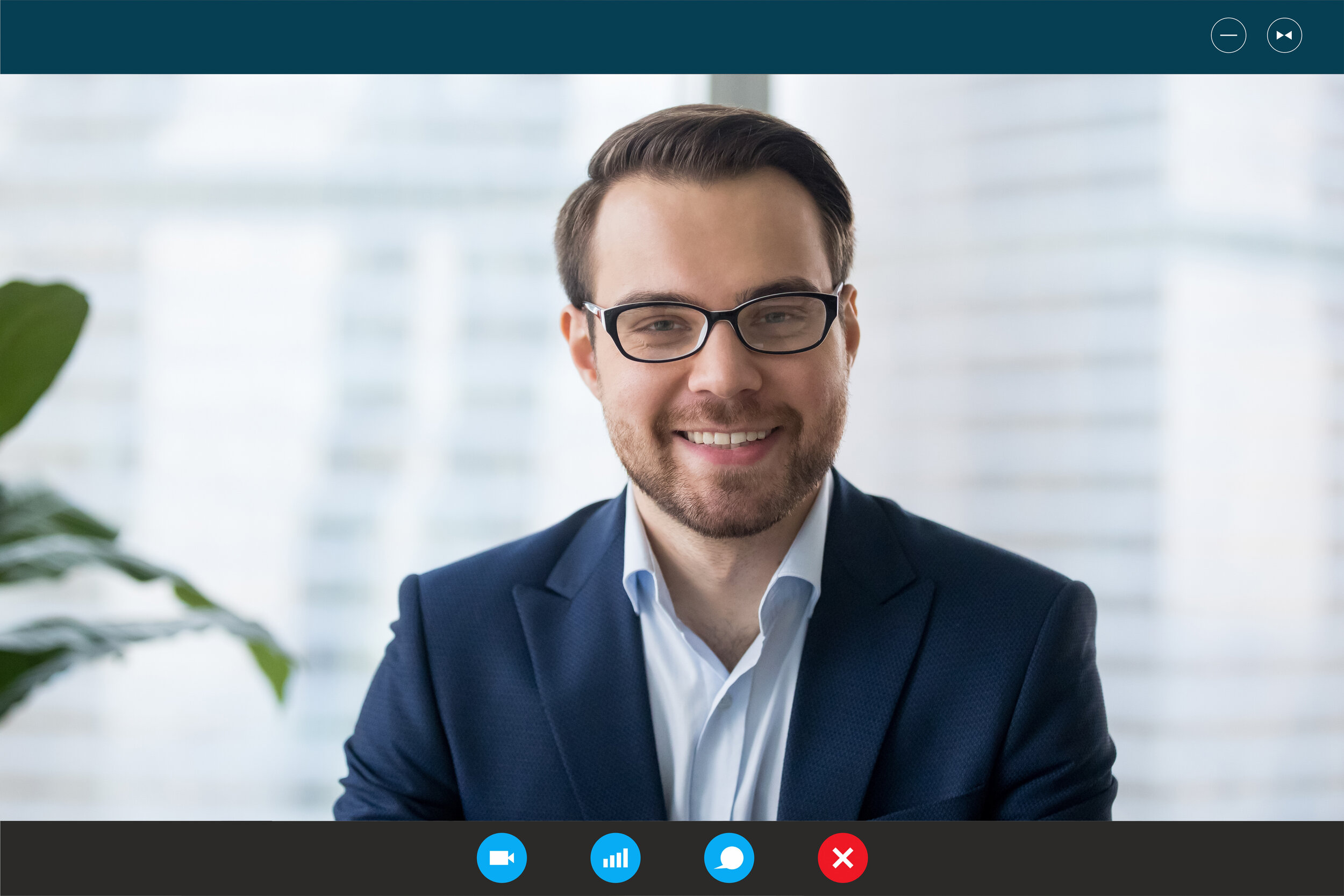

When you place your camera at eye level, good things happen! (1) You talk directly to people (not “down” to them). (2) You can use natural hand gestures in the bottom 1/3 of the screen. (3) Your body language underscores your message. (Upright posture says, “I’m present! I’m listening!” Slouching or leaning back deep in your chair says, “This is my 6th Zoom today … I don’t really want to be here.”

Last week I watched a webinar hosted by a professor at Harvard Business School. She was sharing some ground-breaking research and I was eager to learn about her findings. The material she presented was exceptional and she was clearly a rising star on the faculty.

There was only one problem: how she delivered the material. As I explain in this short video clip, her camera lens was too high. She peered up at us, the audience, from the bottom of her screen. It reminded me of being back in kindergarten at Birch Meadow Elementary School. Imagine me, a scrawny little thing, staring up at my teacher’s big desk — a wooden behemoth stacked even higher with papers and a globe. Walking up to that desk felt intimidating.

The Harvard prof reminded me of staring up at an authority figure. Only in this case, she was looking up at us, the audience. We were peering down on her from above. She’d flipped the script, inverting the position of teacher/student or expert/audience. The result? It felt like she was asking our permission to speak rather than commanding our attention. The placement of her camera had undermined her credibility.

Societal norms explain why.

In western culture, authority figures often physically and literally loom above us. Judges sit high on a platform. (Think the Supreme Court.) Speakers deliver remarks from a stage to an audience seated below. In Congressional hearings, elected officials sit high up in chairs beaming down on the individual testifying on the Senate floor below.

Another common mistake with camera placement is the opposite of what we’ve been talking about: people peering down at their audience. Here’s a short video example of staring down at your device. Let’s face it: no one wants to be looked down upon.

C-suiters who make this mistake further accentuate the existing power imbalance between them and their employees. Said differently, leaders should convince people to embrace their big new idea through evidence and persuasion – never by towering over them, or worse, intimidating them.

When your body language and words don’t match, what happens? People believe your body language. A CEO can talk endlessly about encouraging workers to speak up but, if he talks down to people, he likely won’t elicit much by way of grassroots innovation.

The Take-Away

The ideal placement of your camera is eye level. Look straight ahead at the camera lens itself. Don’t just glance in the general direction of your monitor or laptop. If your camera lens isn’t at eye level, it’s easy to fix it. (Seriously, there’s no need to buy a fancy, expensive tripod.)

If the lens is too low, prop it up with a few books or a sturdy box.

If the lens is too high, simply stand up or move it to another location.

Once you place your camera correctly, your head and body should be in the center of the screen. This will help reduce distractions for your audience and keep your message on center stage. I’d also recommend standing about an arm’s length away from your device. (Think formal cocktail party.) This will create enough space between your device and your body to use more effective hand gestures, which should show up naturally in the bottom third of the picture frame.

All told, moving your camera to eye level will pay off handsomely in your next online presentation. You’ll not only look more polished and in command of your content. You’ll come across as a more credible speaker who talks “to” and “with” people instead of down to them.

![When people tell a moving story, our brains release cortisol and oxytocin. [Photo Credit: Paul Zak video, “The Future of Storytelling”]](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/56b15eefb6aa6091b8ce7fc2/1569261110558-R9NQ7JJKY3H34V7KXJOM/Rosemary+Sept+blog+photo.png)

![Statistics and data won’t move your audience to action – but stories will. [Photo Credit: Annie Spratt]](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/56b15eefb6aa6091b8ce7fc2/1567705993438-BN7632JISAQGFOE4U3OT/Rose+Sept+Blog+Photo.png)

![Don’t use slides as a reminder of what comes next (as in, ‘Oh yeah — the slide w/ the stars. That’s my cue to talk about space’). Instead figure out what you want to say, then build your slide deck. [Photo credit: Kyle Wong]](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/56b15eefb6aa6091b8ce7fc2/1558381268679-QWKDWRJCWN47G45686C9/kyle-wong-146260-unsplash.jpg)

![In the end, the stakes are just too high not to practice. [Photo credit: Charles Deluvio]](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/56b15eefb6aa6091b8ce7fc2/1535128273449-L5MOGYBEV0FU39G8ZGW3/charles-deluvio-550068-unsplash.jpg)

![The Telephone Test is an easy tool to help you communicate more clearly & concisely. [Photo Credit: rawpixel]](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/56b15eefb6aa6091b8ce7fc2/1528761358908-A56NM0NBG8FZJS0A21NK/rawpixel-659505-unsplash.jpg)

![[Photo Credit: Karla Alexander]](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/56b15eefb6aa6091b8ce7fc2/1521586628501-AUZDGWXNALYG3FWKPNZ7/karla-alexander-190886-unsplash.jpg)